- Volvo

- Ronin

- Black Jesuz / Makaveli / Photography

- Jean Francois Richet

- Lyrics / Composition / World Log

- Andreas . P . Design & Modellierungs Corp. LTD

- World / Transcontinental Art / Works / Creation / Culture

- Coral Reefs / Ocean / Geoecology / Green Environment / Nature

- Fashion / Mode / Vogue

- Finance

- Modellierung & Design 1

- PDF / Portable Document Formats / Protocolations

- Slipknot

- Images / High DPI

- Photography From Me

- Kurt Cobain

- Establishment / Industry & Corporation Language

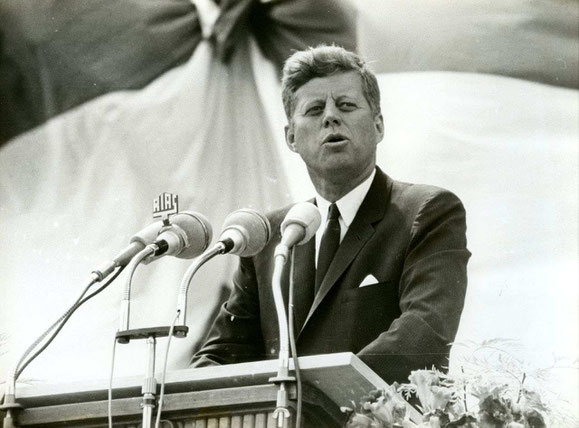

- John F. Kennedy / Documentary / US / Archive

- Justice & Law Terms / Bloomberg / Different Resources from World / Journalism

- Medicine / Development / Technology / Economically Intelligent Future / Silk Road / ( China )

- Gangs of New York

- Portable Document Formats / Protocolations / Diversification

- Modellierung & Design 3

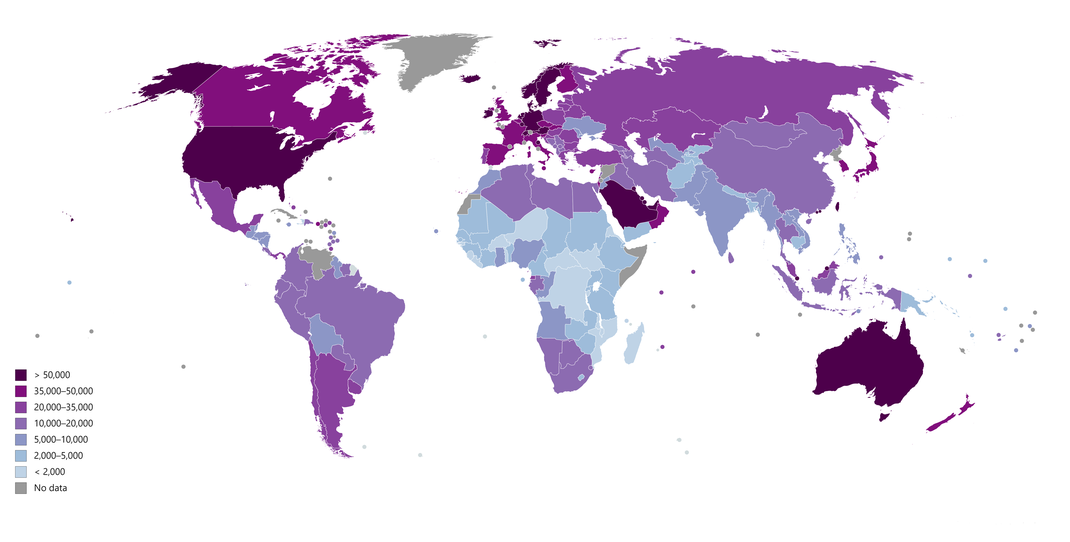

- World Economic Model

- M & D 4

- Modellierung & Design 5

- World ( ISS ) Intergalactic Space Exploring ( Universe ) System (A.P.P)

- Germany Native ( DE ) Blog Comprehensive

- ( World ) Active Grand Colosseum ( Sports ) Initiative

- Ideas Commission / World Statement / Archive / Sourcing

- PDF / Diversification / Formats - No.3

- United States of America ( USA ) World Affairs

- World Economic Model 2 ( Flexible Growth Budgeting ) News

- ( M & D ) 6

- Modellierung & Design 7

- ( M & D ) 8 / Multiplex Blogspot

John F. Kennedy / USA / Article / Brochure / Resource / Library

Shortly after noon on November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated as he rode in a motorcade through Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas, Texas.

By the fall of 1963, President John F. Kennedy and his political advisers were preparing for the next presidential campaign. Although he had not formally announced his candidacy, it was clear that President Kennedy was going to run and he seemed confident about his chances for re-election.

At the end of September, the president traveled west, speaking in nine different states in less than a week. The trip was meant to put a spotlight on natural resources and conservation efforts. But JFK also used it to sound out themes—such as education, national security, and world peace—for his run in 1964.

Campaigning in Texas

A month later, the president addressed Democratic gatherings in Boston and Philadelphia. Then, on November 12, he held the first important political planning session for the upcoming election year. At the meeting, JFK stressed the importance of winning Florida and Texas and talked about his plans to visit both states in the next two weeks.President Kennedy in a group of people in Forth Worth, Texas Mrs. Kennedy would accompany him on the swing through Texas, which would be her first extended public appearance since the loss of their baby, Patrick, in August. On November 21, the president and first lady departed on Air Force One for the two-day, five-city tour of Texas.

Presidential motorcade in Dallas, Texas, 22 November 1963 President Kennedy was aware that a feud among party leaders in Texas could jeopardize his chances of carrying the state in 1964, and one of his aims for the trip was to bring Democrats together. He also knew that a relatively small but vocal group of extremists was contributing to the political tensions in Texas and would likely make its presence felt—particularly in Dallas, where US Ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson had been physically attacked a month earlier after making a speech there. Nonetheless, JFK seemed to relish the prospect of leaving Washington, getting out among the people and into the political fray.

The first stop was San Antonio. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Governor John B. Connally, and Senator Ralph W. Yarborough led the welcoming party. They accompanied the president to Brooks Air Force Base for the dedication of the Aerospace Medical Health Center. Continuing on to Houston, he addressed a Latin American citizens' organization and spoke at a testimonial dinner for Congressman Albert Thomas before ending the day in Fort Worth.

Morning in Fort Worth

Kennedy speaks at rally in Fort Worth, Texas

A light rain was falling on Friday morning, November 22, but a crowd of several thousand stood in the parking lot outside the Texas Hotel where the Kennedys had spent the night. A platform was set up and the president, wearing no protection against the weather, came out to make some brief remarks. "There are no faint hearts in Fort Worth," he began, "and I appreciate your being here this morning. Mrs. Kennedy is organizing herself. It takes longer, but, of course, she looks better than we do when she does it." He went on to talk about the nation's need for being "second to none" in defense and in space, for continued growth in the economy and "the willingness of citizens of the United States to assume the burdens of leadership."

The warmth of the audience response was palpable as the president reached out to shake hands amidst a sea of smiling faces.

Back inside the hotel the president spoke at a breakfast of the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, focusing on military preparedness. "We are still the keystone in the arch of freedom," he said. "We will continue to do…our duty, and the people of Texas will be in the lead."

On to Dallas

The presidential party left the hotel President and Mrs. Kennedy at Love Field, Dallas, Texas and went by motorcade to Carswell Air Force Base for the thirteen-minute flight to Dallas. Arriving at Love Field, President and Mrs. Kennedy disembarked and immediately walked toward a fence where a crowd of well-wishers had gathered, and they spent several minutes shaking hands.

The first lady received a bouquet of red roses, which she brought with her to the waiting limousine. Governor John Connally and his wife, Nellie, were already seated in the open convertible as the Kennedys entered and sat behind them. Since it was no longer raining, the plastic bubble top had been left off. Vice President and Mrs. Johnson occupied another car in the motorcade.The procession left the airport and traveled along a ten-mile route that wound through downtown Dallas on the way to the Trade Mart where the President was scheduled to speak at a luncheon.

The Assassination

Crowds of excited people lined the streets and waved to the Kennedys. The car turned off Main Street at Dealey Plaza around 12:30 p.m. As it was passing the Texas School Book Depository, gunfire suddenly reverberated in the plaza.

Bullets struck the president's neck and head and he slumped over toward Mrs. Kennedy. The governor was also hit in the chest.

President Lyndon B. Johnson takes Oath of Office

The car sped off to Parkland Memorial Hospital just a few minutes away. But little could be done for the President. A Catholic priest was summoned to administer the last rites, and at 1:00 p.m. John F. Kennedy was pronounced dead. Though seriously wounded, Governor Connally would recover.

The president's body was brought to Love Field and placed on Air Force One. Before the plane took off, a grim-faced Lyndon B. Johnson stood in the tight, crowded compartment and took the oath of office, administered by US District Court Judge Sarah Hughes. The brief ceremony took place at 2:38 p.m.

Less than an hour earlier, police had arrested Lee Harvey Oswald, a recently hired employee at the Texas School Book Depository. He was being held for the assassination of President Kennedy and the fatal shooting, shortly afterward, of Patrolman J. D. Tippit on a Dallas street.

On Sunday morning, November 24, Oswald was scheduled to be transferred from police headquarters to the county jail. Viewers across America watching the live television coverage suddenly saw a man aim a pistol and fire at point blank range. The assailant was identified as Jack Ruby, a local nightclub owner. Oswald died two hours later at Parkland Hospital.

The President's Funeral

That same day, President Kennedy's flag-draped casket was moved from the White House to the Capitol on a caisson drawn by six grey horses, accompanied by one riderless black horse. At Mrs. Kennedy's request, the cortege and other ceremonial details were modeled on the funeral of Abraham Lincoln. Crowds lined Pennsylvania Avenue and many wept openly as the caisson passed. During the 21 hours that the president's body lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda, about 250,000 people filed by to pay their respects.

President Kennedy Lies in Repose at White HouseOn Monday, November 25, 1963 President Kennedy was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. The funeral was attended by heads of state and representatives from more than 100 countries, with untold millions more watching on television. Afterward, at the grave site, Mrs. Kennedy and her husband's brothers, Robert and Edward, lit an eternal flame.

Perhaps the most indelible images of the day were the salute to his father given by little John F. Kennedy Jr. (whose third birthday it was), daughter Caroline kneeling next to her mother at the president's bier, and the extraordinary grace and dignity shown by Jacqueline Kennedy.

As people throughout the nation and the world struggled to make sense of a senseless act and to articulate their feelings about President Kennedy's life and legacy, many recalled these words from his inaugural address:

All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days, nor in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this administration. Nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin.

The Warren Commission

On November 29, 1963 President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy. It came to be known as the Warren Commission after its chairman, Earl Warren, Chief Justice of the United States. President Johnson directed the commission to evaluate matters relating to the assassination and the subsequent killing of the alleged assassin, and to report its findings and conclusions to him.

The House Select Committee on Assassinations

The US House of Representatives established the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1976 to reopen the investigation of the assassination in light of allegations that previous inquiries had not received the full cooperation of federal agencies.

The Assassination of John F. Kennedy

At precisely 1pm on November 22, 1963, the 35th president of the United States was pronounced dead at Parkland Hospital Trauma Room 1 in Dallas, Texas.

John F Kennedy’s personal physician stated the cause of death was a gunshot wound to the head. This was officially announced to a stunned public half an hour later. The shock waves of the president’s assassination, the fourth in US history, continue to reverberate today.

While the events of that day have been the subject of numerous conspiracy theories, the basic facts are now widely accepted. The president’s motorcade was making its way through Dealey Plaza in downtown Dallas when, five minutes from its destination, three shots rang out from behind and above the presidential limousine.

Two of those shots found their mark, with the second being fatal. Texas’s Democratic governor, John Connally, who was seated immediately in front of the president, was also hit, though he would recover from his injuries.

Seventy minutes after the attack, Dallas police arrested Lee Harvey Oswald, a former US marine who had spent three years in the Soviet Union. However, before Oswald could be properly questioned on his motives, less than 48 hours after the assassination of the president, Oswald himself was also dead.

He was gunned down on live television by Jack Ruby, a Dallas nightclub owner with links to organised crime. This inspired generations of conspiracy theorists for whom the Kennedy assassination was an expression of unidentified malevolent forces threatening the United States.

One of the most ubiquitous and apparently plausible of the conspiracy theories floating around was that there was a second gunman, and that both he and Oswald were part of a wider circle of conspirators.

Despite the Warren Commission, which had been set up by new President Lyndon Johnson to investigate Kennedy’s murder, stating in September 1964 that Oswald was a “lone gunman” and was not part of any domestic or international conspiracy, this conclusion was not widely accepted until the mid 1970s.

Several developments that cast doubt on the lone gunman thesis include a Senate Select Committee established to investigate “Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities” in 1975. It asserted that investigations of the assassination by both the FBI and CIA had been deficient, and that some fundamental evidence had not been forwarded to the original Warren Commission.

Furthermore, Abraham Zapruder’s now famous 26-second silent home movie of the killing was also released to public scrutiny in 1975.

To the untrained eye, the film seems to show that the fatal second shot came from the front of the president’s car. His head snaps back and bodily matter is projected to the rear. Viewed in conjunction with conclusions from the Senate and House Committees, this was presumed by many to validate the claim that a second shooter had fired from the infamous “grassy knoll” to the right and front of the presidential cavalcade.

Subsequently, the theory that a second assassin fired a fourth shot was conclusively falsified. The United States House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) had acquired a police radio channel dicta belt recording of a motorcycle officer who had been part of the cavalcade. When this evidence was reexamined by independent acoustic research experts, they unanimously agreed that the apparent fourth shot was not a shot at all.

Similarly, after reviewing the evidence, ballistic, forensic and medical experts have repeatedly drawn the conclusion that the entry and exit wounds on the president were consistent with having been shot from the rear rather than the front.

So we can conclude with a very high degree of certainty that Oswald was the sole gunman who shot Kennedy. But it does not follow that the conception and planning of the assassination was that of Oswald’s alone.

As a result of renewed interest generated by the Oliver Stone film, JFK, Congress passed the JFK Act in 1992. This led to the public release of over 4 million pages of documents pertaining to the assassination.

It was on the basis of an exhaustive analysis of this material, in conjunction with all of the earlier government reports and secondary literature, that David Kaiser published the first book about the assassination written by a professional historian with all of the archival evidence available to him.

The Road to Dallas: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy cites archival evidence that firmly links Oswald to a network of organised crime figures, anti-Castro Cubans and far-right political activists, all of whom had motives for wanting the president dead. While its conclusions are not watertight, the book’s judicious judgements provide the most compelling account yet that Oswald acted as part of a broader conspiracy.

Kaiser’s essential argument is that a cabal of organised crime figures and anti-Castro Cuban exiles most likely recruited Oswald to be the trigger man in an attempt on the president’s life.

The interests of organised crime figures, many of whom had had commercial operations in Cuba disrupted by the revolution, coincided with those of wealthy anti-Castro Cubans who had been exiled to the United States.

Both groups were profoundly hostile to Kennedy and his brother, Attorney-General Robert Kennedy. Their administration had not only failed to invade Cuba and restore mob and Cuban private property, it had also waged a relentless campaign against particular organised crime figures.

Where once Nixon and Reagan spoke in the coded racial language of states’ rights, Trump now speaks in the forthright language of stopping Muslim immigration, kicking out Mexican murderers and rapists, and building walls between us and them.

The vindictive, emotional politics of fear and rage is his standard currency. He has concentrated in his rhetoric and actions the most noxious elements of American politics in the half century that has passed since Kennedy’s untimely death.

The political reverberations of the Kennedy assassination, then, continue to be felt in all sorts of unlikely ways.

The paranoid, racialised and faux anti-elitist politics of the American right did not begin with the backlash against Kennedy and his administration. But his presidency and assassination, and the anxious political forces it set in motion, are an important milestone in their development. The American right today, with Trump as its figurehead, is the direct political descendant of this dark chapter in American history.

There is solid evidence that Oswald had direct or indirect contact with at least two such figures, while also being in contact with a wider group of anti-Castro activists.Kaiser surmises that the overlapping networks of mobsters and Cuban exiles hoped that the assassination of Kennedy, for which Oswald would be paid handsomely, would provoke a US invasion of Cuba and the restoration of their private property and commercial operations.This, of course, did not happen. Instead, there was a very different set of short and long term consequences.

In the short term, the new president, Johnson, seized the opportunity offered by a nation’s grief to crush the Republican challenge at the 1964 election. He used that result as a mandate to vigorously pursue his liberal, Great Society programme and civil rights agenda, which greatly expanded the role of government and advanced the rights of African-Americans and other ethnic minorities.

Longer term, it was Johnson’s liberal programme that provoked a conservative, white backlash that would gather strength under the presidencies of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan.

In the 1968 and 1972 presidential elections, Nixon adopted his infamous “Southern strategy”. It deployed the coded racial language of “states’ rights” to split away white southerners from the Democratic Party whom they had traditionally supported.

Nixon’s law and order rhetoric simultaneously appealed to the anxieties of what he claimed was a “silent majority”, who had been shaken by urban turmoil and the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr. Respectable fears and the politics of race converged with paranoia stoked by conspiracy theories involving all of these assassinations.

This white backlash and the realignment of many white working and middle class Americans to the Republican Party accelerated in the 1980s under President Reagan, and was consummated in the 2000s during the presidencies of George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

A significant sub-section of white America could not reconcile themselves to the legitimacy of a black president after 2008. This expressed itself in the “birther” backlash against Obama, and the generalised hatred that greeted the new president from the political right.

It is that same backlash, albeit taking new forms, that we today witness in the strange spectacle of Donald Trump’s presidency.

Trump had been a central protagonist in the birther controversy, and has consistently played on race-based fears and prejudice to energise his supporters.

John F. Kennedy / 35th President of the ( USA ) North America / By Example one of greatest Presidents in History Books of USA / America / One of the most famous Politicians in World History

FACTS, INFORMATION AND ARTICLES ABOUT JOHN F. KENNEDY, THE 35TH U.S. PRESIDENT

JOHN F. KENNEDY FACTS

BORN

5/29/1917

DIED

11/22/1963

SPOUSE

Jacqueline Bouvier

YEARS OF MILITARY SERVICE

1941-1945

RANK

Lieutenant

ACCOMPLISHMENTS

Navy and Maine Corps Medal

Purple Heart

American Campaign Medal

Asiatio-Pacific Campaign Medal

World War II Victory Medal

35th President Of the United States

JOHN F. KENNEDY ARTICLES

John F. Kennedy summary: John F. Kennedy was the 35th president of the United States. He was born in 1917 into a wealthy family with considerable political ties. Kennedy studied Political Science at Harvard University. He later served as a lieutenant in the Navy, where he earned a Purple Heart, among other honors, during World War II. After leaving the Navy, Kennedy worked as a journalist for several years. He later went on to serve three terms in House of Representatives, followed by a term as senator from 1953 to 1961. He wrote a Pulitzer Prize–winning book, Profiles in Courage. In 1953, he married Jacqueline “Jackie” Bouvier, a photographer-columnist for the Washington Times-Herald. The couple came to be regarded almost as American royalty; he was popular due to his charm, good looks, and vitality, and Jackie became an icon of fashion and grace who was active in promoting the arts and historic preservation. In 1960, Kennedy won the presidential election by a very narrow margin but carried the electoral college 303–219, beating Richard Nixon to become the 35th president of the United States. He was the youngest man and first Catholic to hold that office.

During his presidency, Kennedy gave many inspiring speeches; these speeches, rather than his legislative accomplishments, became his legacy. He did help to further the civil rights movement, but most of the legislature he initiated did not become law during his presidency. On November 22, 1963, John F. Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas, Texas. His assassination raised questions of a possible conspiracy that are still being debated today. His life and death have been the subject of numerous books, documentaries and feature films.

The most famous collision in U.S. Navy history occurred at about 2:30 a.m. on August 2, 1943, a hot, moonless night in the Pacific. Patrol Torpedo boat 109 was idling in Blackett Strait in the Solomon Islands. The 80-foot craft had orders to attack enemy ships on a resupply mission. With virtually no warning, a Japanese destroyer emerged from the black night and smashed into PT-109, slicing it in two and igniting its fuel tanks. The collision was part of a wild night of blunders by 109 and other boats that one historian later described as “the most screwed up PT boat action of World War II.” Yet American newspapers and magazines reported the PT-109 mishap as a triumph. Eleven of the 13 men aboard survived, and their tale, declared the Boston Globe, “was one of the great stories of heroism in this war.” Crew members who were initially ashamed of the accident found themselves depicted as patriots of the first order, their behavior a model of valor.

The PT-109 disaster made JFK a hero. But his fury and grief at the loss of two men sent him on a dangerous quest to get even.

The Globe story and others heaped praise on Lieutenant (j.g.) John F. Kennedy, commander of the 109 and son of the millionaire and former diplomat Joseph Kennedy. KENNEDY’S SON IS HERO IN PACIFIC AS DESTROYER SPLITS HIS PT BOAT, declared a New York Times headline. It was Kennedy’s presence, of course, that made the collision big news. And it was his father’s media savvy that helped turn an embarrassing disaster into a tale worthy of Homer.

Airbrushed from this PR confection was Lieutenant Kennedy’s reaction to the accident. The young officer was deeply pained by the death of two of his men in the collision. Returning to duty in command of a new breed of PT boat, he lobbied for dangerous assignments and displayed a recklessness that worried fellow officers. Kennedy, they said, was hell-bent on redeeming himself and getting revenge on the Japanese.

Kennedy would later embrace the myths of PT-109 and ride them into the White House. But in his last months in combat, he appeared to be a troubled young man trying to make peace with what happened that dark night in the Solomons.

Jack Kennedy was sworn in as an ensign on September 25, 1941. At 24, he was already something of a celebrity. With financial backing from his father and the help of New York Times columnist Arthur Krock, he had turned his 1939 Harvard thesis into Why England Slept, a bestseller about Britain’s failure to rearm to meet the threat of Hitler.

Getting young Jack into the navy took similar finagling. As one historian put it, Kennedy’s fragile health meant he was not qualified for the Sea Scouts, much less the U.S. Navy. From boyhood, he had suffered from chronic colitis, scarlet fever, and hepatitis. In 1940, the U.S. Army’s Officer Candidate School had rejected him as 4-F, citing ulcers, asthma, and venereal disease. Most debilitating, doctors wrote, was his birth defect—an unstable and often painful back.

When Jack signed up for the navy, his father pulled strings to ensure his poor health did not derail him. Captain Alan Goodrich Kirk, head of the Office of Naval Intelligence, had been the naval attaché in London before the war when Joe Kennedy had served as ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. The senior Kennedy persuaded Kirk to let a private Boston doctor certify Jack’s good health.

Kennedy was soon enjoying life as a young intelligence officer in the nation’s capital, where he started keeping company with 28-year-old Inga Marie Arvad, a Danish-born reporter already twice married but now separated from her second husband, a Hungarian film director. They had a torrid affair—many biographers say she was the true love of Kennedy’s life—but the relationship became a threat to his naval career. Arvad had spent time reporting in Berlin and had grown friendly with Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, and other prominent Nazis—ties that raised suspicions she was a spy.

Kennedy eventually broke up with Arvad, but the imbroglio left him depressed and exhausted. He told a friend he felt “more scrawny and weak than usual.” He developed excruciating pain in his lower back. Jack consulted with his doctor at the Lahey Clinic in Boston, and asked for a six-month leave for surgery. Lahey doctors as well as specialists at the Mayo Clinic diagnosed chronic dislocation of the right sacroiliac joint, which could only be cured by spinal fusion.

Navy doctors weren’t so sure that Kennedy needed surgery. He spent two months at naval hospitals, after which his problem was incorrectly diagnosed as muscle strain. The treatment: exercise and medication.

During Jack’s medical leave, the navy won the battles of Midway and the Coral Sea. Ensign Kennedy emerged from his sickbed ferociously determined to see action. He persuaded Undersecretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal, an old friend of his father, to get him into Midshipman’s School at Northwestern University. Arriving in July 1942, he plunged into two months of studying navigation, gunnery, and strategy.

During that time, Lieutenant Commander John Duncan Bulkeley visited the school. Bulkeley was a freshly minted national hero. As commander of a PT squadron, he had whisked General Douglas MacArthur and family from the disaster at Bataan, earning a Medal of Honor and fame in the book They Were Expendable. Bulkeley claimed his PTs had sunk a Japanese cruiser, a troopship, and a plane tender in the struggle for the Philippines, none of which was true. He was now touring the country promoting war bonds and touting the PT fleet as the Allies’ key to victory in the Pacific.

At Northwestern, Bulkeley’s tales of adventure inspired Kennedy and nearly all his 1,023 classmates to volunteer for PT duty. Although only a handful were invited to attend PT training school in Melville, Rhode Island, Kennedy was among them. Weeks earlier, Joe Kennedy had taken Bulkeley to lunch and made it clear that command of a PT boat would help his son launch a political career after the war.

Once in Melville, Jack realized that Bulkeley had been selling a bill of goods. Instructors warned that in a war zone, PTs must never leave harbor in daylight. Their wooden hulls could not withstand even a single bullet or bomb fragment. The tiniest shard of hot metal might ignite the 3,000-gallon gas tanks. Worse, their 1920s-vintage torpedoes had a top speed of only 28 knots—far slower than most of the Japanese cruisers and destroyers they would target. Kennedy joked that the author of They Were Expendable ought to write a sequel titled They Are Useless.

On April 14, 1943, having completed PT training, Kennedy arrived on Tulagi, at the southern end of the Solomon Islands. Fifteen days later, he took command of PT-109. American forces had captured Tulagi and nearby Guadalcanal, but the Japanese remained entrenched on islands to the north. The navy’s task: Stop enemy attempts to reinforce and resupply these garrisons.

Except for the executive officer—Ensign Leonard Thom, a 220-pound former tackle at Ohio State—PT-109’s crew members were all as green as Kennedy. The boat was a wreck. Its three huge Packard motors needed a complete overhaul. Scum fouled its hull. The men worked until mid-May to ready it for sea. Determined to prove he was not spoiled, Jack joined his crew scraping and painting the hull. They liked his refusal to pull rank. They liked even more the ice cream and treats that the lieutenant bought them at the PX. Jack also made friends with his squadron’s commanding officer, 24-year-old Alvin Cluster, one of the few Annapolis graduates to volunteer for the PTs. Cluster shared Jack’s sardonic attitude toward the protocol and red tape of the “Big Navy.”

On May 30, Cluster took PT-109 with him when he was ordered to move two squadrons 80 miles north to the central Solomons. Here Kennedy made a reckless gaffe. After patrols, he liked to race back to base to snare the first spot in line for refueling. He would approach the dock at top speed, reversing his engines only at the last minute. Machinist’s Mate Patrick “Pop” McMahon warned that the boat’s war-weary engines might conk out, but Kennedy paid no heed. One night, the engines finally did fail, and the 109 smashed into the dock like a missile. Some commanders might have court-martialed Kennedy on the spot. But Cluster laughed it off, particularly when his friend earned the nickname “Crash” Kennedy. Besides, it was a mild transgression compared to the blunders committed by other PT crews, whom Annapolis grads called the Hooligan Navy. [See sidebar “The Truth About “Devil Boats.”]

On July 15, three months after Kennedy arrived in the Pacific, PT-109 was ordered to the central Solomons and the island of Rendova, close to heavy fighting on New Georgia. Seven times in the next two weeks, 109 left its base on Lumbari Island, a spit of land in the Rendova harbor, to patrol. It was tense, exhausting work. Though PTs patrolled only at night, Japanese floatplane crews could spot their phosphorescent wakes. The planes often appeared without warning, dropped a flare, and then followed with bombs. Japanese barges, meanwhile, were equipped with light cannons far superior to the PTs’ machine guns and single 20mm gun. Most unnerving were the enemy destroyers running supplies and reinforcements to Japanese troops in an operation the Americans called the Tokyo Express. Cannons from these ships could blast the PTs into splinters.

On one patrol, a Japanese floatplane spotted the PT-109. A near miss showered the boat with shrapnel that slightly wounded two of the crew. Later, floatplane bombs bracketed another PT boat and sent the 109 skittering away in frantic evasive maneuvers. One of the crew, 25-year-old Andrew Jackson Kirksey, became convinced he was going to die and unnerved others with his morbid talk. To increase the boat’s firepower, Kennedy scrounged up a 37mm gun and fastened it with rope on the forward deck. The 109’s life raft was discarded to make room.

Finally came the climactic night of August 1 and 2, 1943. Lieutenant Commander Thomas Warfield, an Annapolis graduate, was in charge at the base on Lumbari. He received a flash message that the Tokyo Express was coming out from Rabaul, the Japanese base far to the north on New Guinea. Warfield dispatched 15 boats, including PT-109, to intercept, organizing the PTs into four groups. Riding with Kennedy was Ensign Barney Ross, whose boat had recently been wrecked. That brought the number of men aboard to 13—a number that spooked superstitious sailors.

Lieutenant Hank Brantingham, a PT veteran who had served with Bulkeley in the famous MacArthur rescue, led the four boats in Kennedy’s group. They motored away from Lumbari at about 6:30 p.m., heading northwest to Blackett Strait, between the small island of Gizo and the bigger Kolombangara. The Tokyo Express was headed to a Japanese base at the southern tip of Kolombangara.

A few minutes after midnight, with all four boats lying in wait, Brantingham’s radar man picked up blips hugging the coast of Kolombangara. The Tokyo Express was not expected for another hour; the lieutenant concluded the radar blips were barges. Without breaking radio silence, he charged off to engage, presuming the others would follow. The nearest boat, commanded by veteran skipper William Liebenow, joined him, but Kennedy’s PT-109 and the last boat, with Lieutenant John Lowrey at the helm, somehow got left behind.

Opening his attack, Brantingham was surprised to discover his targets were destroyers, part of the Tokyo Express. High-velocity shells exploded around his boat as well as Liebenow’s. Brantingham fired his torpedoes but missed. At some point, one of his torpedo tubes caught fire, illuminating his boat as a target. Liebenow fired twice and also missed. With that, the two American boats made a hasty retreat.

Kennedy and Lowrey remained oblivious. But they were not the only patrol stumbling around in the dark. The 15 boats that had left Lumbari that evening fired at least 30 torpedoes, yet hit nothing. The Tokyo Express steamed through Blackett Strait and unloaded 70 tons of supplies and 900 troops on Kolombangara. At about 1:45 a.m., the four destroyers set out for the return trip to Rabaul, speeding north.

Kennedy and Lowrey remained in Blackett Strait, joined now by a third boat, Lieutenant Phil Potter’s PT-169, which had lost contact with its group. Kennedy radioed Lumbari and was told to try to intercept the Tokyo Express on its return.

With the three boats back on patrol, a PT to the south spotted one of the northbound destroyers and attacked, without success. The captain radioed a warning: The destroyers are coming. At about 2:30 a.m., Lieutenant Potter in PT-169 saw the phosphorescent wake of a destroyer. He later said that he, too, radioed a warning.

Aboard PT-109, however, there was no sense of imminent danger. Kennedy received neither warning, perhaps because his radioman, John Maguire, was with him and Ensign Thom in the cockpit. Ensign Ross was on the bow as a lookout. McMahon, the machinist’s mate, was in the engine room. Two members of the crew were asleep, and two others were later described as “lying down.”

Harold Marney, stationed at the forward turret, was the first to see the destroyer. The Amagiri, a 2,000-ton ship four times longer than the 109, emerged out of the black night on the starboard side, about 300 yards away and bearing down. “Ship at two o’clock!” Marney shouted.

Kennedy and the others first thought the dark shape was another PT boat. When they realized their mistake, Kennedy signaled the engine room for full power and spun the ship’s wheel to turn the 109 toward the Amagiri and fire. The engines failed, however, and the boat was left drifting. Seconds later, the destroyer, traveling at 40 knots, slammed into PT-109, slicing it from bow to stern. The crash demolished the forward gun turret, instantly killing Marney and Andrew Kirksey, the enlisted man obsessed with his death.

In the cockpit, Kennedy was flung violently against the bulkheads. Prone on the deck, he thought: This is how it feels to be killed. Gasoline from the ruptured fuel tanks ignited. Kennedy gave the order to abandon ship. The 11 men leaped into the water, including McMahon, who had been badly burned as he fought his way to the deck through the fire in the engine room.

After a few minutes, the flames from the boat began to subside. Kennedy ordered everyone back aboard the part of the PT-109 still afloat. Some men had drifted a hundred yards into the darkness. McMahon was almost helpless. Kennedy, who’d been on the Harvard swim team, took charge of him and pulled him back to the boat.

Dawn found the men clinging to the tilting hulk of PT-109, which was dangerously close to Japanese-controlled Kolombangara. Kennedy pointed toward a small bit of land about four miles away—Plum Pudding Island—that was almost certainly uninhabited. “We’ve got to swim to that,” he said.

They set out from the 109 around 1:30 p.m. Kennedy towed McMahon, gripping the strap of the injured man’s life jacket in his teeth. The journey took five exhausting hours, as they fought a strong current. Kennedy reached the beach first and collapsed, vomiting salt water.

Worried that McMahon might die from his burns, Kennedy left his crew near sundown to swim into Ferguson Passage, a feeder to Blackett Strait. The men begged him not to take the risk, but he hoped to find a PT boat on a night patrol. The journey proved harrowing. Stripped to his underwear, Kennedy walked along a coral reef that snaked far out into the sea, perhaps nearly to the strait. Along the way, he lost his bearings, as well as his lantern. At several points, he had to swim blindly in the dark.

Back on Plum Pudding Island, the men had nearly given their commander up for dead when he stumbled across the reef at noon the next day. It was the first of several trips that Kennedy made into Ferguson Passage to find help. Each failed. But his courage earned the lieutenant his men’s loyalty for life.

Over the next few days, Kennedy put up a brave front, talking confidently of their rescue. When Plum Pudding’s coconuts—their only food—ran short, he moved the survivors to another island, again towing McMahon through the water.

Eventually, the men were found by two natives who were scouts for a coastwatcher, a New Zealand reserve officer doing reconnaissance. Their rescue took time to engineer, but at dawn on August 8, six days after the 109 was hit, a PT boat pulled into the American base carrying the 11 survivors.

On board were two wire-service reporters who had jumped at the chance to report on the rescue of the son of Joseph Kennedy. Their stories and others exploded in newspapers, with dramatic accounts of Kennedy’s exploits. But the story that would define the young officer as a hero ran much later, after his return to the States in January 1944.

By chance, Kennedy met up for drinks one night at a New York nightclub with writer John Hersey, an acquaintance who had married one of Jack’s former girlfriends. Hersey proposed doing a PT-109 story for Life magazine. Kennedy consulted his father the next day. Joe Kennedy, who hoped to secure his son a Medal of Honor, loved the idea.

The 29-year-old Hersey was an accomplished journalist and writer. His first novel, A Bell for Adano, was published the same week he met Kennedy at the nightclub; it would win a Pulitzer in 1945. Hersey had big ambitions for the PT-109 article; he wanted to use devices from fiction in a true-life story. Among the tricks to try out: telling the story from the perspective of the people involved and lingering on their feelings and emotions—something frowned upon in journalism of the day. In his retelling of the PT-109 disaster, the crew members would be like characters in a novel.

Kennedy, of course, was the protagonist. Describing his swim into the Ferguson Passage from Plum Pudding Island, Hersey wrote: “A few hours before he had wanted desperately to get to the base at [Lumbari]. Now he only wanted to get back to the little island he had left that night….His mind seemed to float away from his body. Darkness and time took the place of a mind in his skull.”

Life turned down Hersey’s literary experiment—probably because of its length and novelistic touches—but the New Yorker published the story in June. Hersey was pleased—it was his first piece for the heralded magazine—but it left Joe Kennedy in a black mood. He regarded the relatively small-circulation New Yorker as a sideshow in journalism. Pulling strings, Joe persuaded the magazine to let Reader’s Digest publish a condensation, which the tony New Yorker never did.

This shorter version, which focused almost exclusively on Jack, reached millions of readers. The story helped launch Kennedy’s political career. Two years later, when he ran for Congress from Boston, his father paid to send 100,000 copies to voters. Kennedy won handily.

That campaign, according to scholar John Hellman, marks the “true beginning” of the Kennedy legend. Thanks to Hersey’s evocative portrait and Joe Kennedy’s machinations, Hellman writes, the real-life Kennedy “would merge with the ‘Kennedy’ of Hersey’s text to become a popular myth.”

Hersey’s narrative devoted remarkably few words to the PT-109 collision itself—at least in part because the writer was fascinated by what Kennedy and his men did to survive. (His interest in how men and women react to life-threatening pressures would later take him to Hiroshima, where he did a landmark New Yorker series about survivors of the nuclear blast.) Hersey also stepped lightly around the question of whether Kennedy was responsible.

The navy’s intelligence report on the loss of the PT-109 was also mum on the subject. As luck would have it, another Kennedy friend, Lieutenant (j.g.) Byron “Whizzer” White, was selected as one of two officers to investigate the collision. An All-America running back in college, White had first met Kennedy when the two were in Europe before the war—White as a Rhodes scholar, Kennedy while traveling. They had shared a few adventures in Berlin and Munich. As president, Kennedy would appoint White to the Supreme Court.

In the report, White and his coauthor described the collision matter-of-factly and devoted almost all the narrative to Kennedy’s efforts to find help. Within the command ranks of the navy, however, Kennedy’s role in the collision got a close look. Though Alvin Cluster recommended his junior officer for the Silver Star, the navy bureaucracy that arbitrates honors chose to put up Kennedy only for the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, a noncombat award. This downgrade hinted that those high up in the chain of command did not think much of Kennedy’s performance on the night of August 2. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox let the certificate confirming the medal sit on his desk for several months.

It wasn’t until fate intervened that Kennedy got his medal: On April 28, 1944, Knox died of a heart attack. Joe Kennedy’s friend James Forrestal—who helped Jack win transfer to the Pacific—became secretary. He signed the medal certificate on the same day that he was sworn in.

In the PT fleet, some blamed “Crash” Kennedy for the collision. His crew should have been on high alert, they said. Warfield, the commander at Lumbari that night, later claimed that Kennedy “wasn’t a particularly good boat commander.” Lieutenant Commander Jack Gibson, Warfield’s successor, was even tougher. “He lost the 109 through very poor organization of his crew,” Gibson later said. “Everything he did up until he was in the water was the wrong thing.”

Other officers blamed Kennedy for the failure of the 109’s engine when the Amagiri loomed into sight. He had been running on only one engine, and PT captains well knew that abruptly shoving the throttles to full power often killed the engines.

There was also the matter of the radio warnings. Twice, other PT boats had signaled that the Tokyo Express was headed north to where the 109 was patrolling. Why wasn’t Kennedy’s radioman below deck monitoring the airwaves?

Some of this criticism can be discounted. Warfield had to answer for mistakes of his own from that wild night. Gibson, who was not even at Lumbari, can be seen as a Monday-morning quarterback. As for the radio messages, Kennedy’s patrol group was operating under an order of radio silence. If the 109 assumed that order banned radio traffic, why bother monitoring the radio?

There’s also a question of whether the navy adequately prepared Kennedy’s men, or any of the PT crews. Though the boats patrolled at night, no evidence suggests they were trained to see long distances in darkness—a skill called night vision. As a sailor aboard the light cruiser Topeka (CL-67) in 1945 and 1946, this writer and his shipmates were trained in the art and science of night vision. The Japanese, who were the first to study this talent, taught a cadre of sailors to see extraordinary distances. At the 1942 night battle of Savo Island, in which the Japanese destroyed a flotilla of American cruisers, their lookouts first sighted their targets almost two and a half miles away.

No one aboard PT-109 knew how to use night vision. With it, Kennedy or one of the others might have picked the Amagiri out of the night sooner.

However valid, the criticism of his command must have reached Kennedy. He might have shrugged off the putdowns of other PT skippers, but it must have been harder to ignore the biting words of his older brother. At the time of the crash, 28-year-old Joe Kennedy Jr. was a navy bomber pilot stationed in Norfolk, Virginia, waiting for deployment to Europe. He was tall, handsome, and—unlike Jack—healthy. His father had long ago anointed him as the family’s best hope to reach the White House.

Joe and Jack were bitter rivals. When Joe read Hersey’s story, he sent his brother a letter laced with barbed criticism. “What I really want to know,” he wrote, “is where the hell were you when the destroyer hove into sight, and exactly what were your moves?”

Kennedy never answered his brother. Indeed, little is known about how he rated his performance on the night of August 2. But there is evidence that he felt enormous guilt—that Joe’s questions struck a nerve. Kennedy had lost two men, and he was clearly troubled by their deaths.

After the rescue boats picked up the 109 crew, Kennedy kept to his bunk on the return to Lumbari while the other men happily filled the notebooks of the reporters on board. Later, according to Alvin Cluster, Kennedy wept. He was bitter that other PT boats had not moved in to rescue his men after the wreck, Cluster said. But there was more.

“Jack felt very strongly about losing those two men and his ship in the Solomons,” Cluster said. “He…wanted to pay the Japanese back. I think he wanted to recover his self-esteem.”

At least one member of the 109 felt humiliated by what happened in Blackett Strait—and was surprised that Hersey’s story wrapped them in glory. “We were kind of ashamed of our performance,” Barney Ross, the 13th man aboard, said later. “I had always thought it was a disaster, but [Hersey] made it sound pretty heroic, like Dunkirk.”

Kennedy spent much of August in sickbay. Cluster offered to send the young lieutenant home, but he refused. He also put a stop to his father’s efforts to bring him home.

By September, Kennedy had recovered from his injuries and was panting for action. About the same time, the navy finally recognized the weaknesses of its PT fleet. Work crews dismantled the torpedo tubes and screwed armor plating to the hulls. New weapons bristled from the deck—two .50-caliber machine guns and two 40mm cannons.

Promoted to full lieutenant in October, Jack became one of the first commanders of the new gunboats, taking charge of PT-59. He told his father not to worry. “I’ve learned to duck,” he wrote, “and have learned the wisdom of the old naval doctrine of keeping your bowels open and your mouth shut, and never volunteering.”

But from late October through early November, Kennedy took the PT-59 into plenty of action from its base on the island of Vella Lavella, a few miles northwest of Kolombangara. Kennedy described those weeks as “packed with a great deal in the way of death.” According to the 59’s crew, their commander volunteered for the riskiest missions and sought out danger. Some balked at going out with him. “My God, this guy’s going to get us all killed!” one man told Cluster.

Kennedy once proposed a daylight mission to hunt hidden enemy barges on a river on the nearby island of Choiseul. One of his officers argued that this was suicide; the Japanese would fire on them from both banks. After a tense discussion, Cluster shelved the expedition. All along, he harbored suspicions that the PT-109 incident was clouding his friend’s judgment. “I think it was the guilt of losing his two crewmen, the guilt of losing his boat, and of not being able to sink a Japanese destroyer,” Cluster said later. “I think all these things came together.”

On November 2, Kennedy saw perhaps his most dramatic action on PT-59. In the afternoon, a frantic plea reached the PT base from an 87-man Marine patrol fighting 10 times that many Japanese on Choiseul. Although his gas tanks were not even half full, Kennedy roared out to rescue more than 50 Marines trapped on a damaged landing craft that was taking on water. Ignoring enemy fire from shore, Kennedy and his crew pulled alongside and dragged the Marines aboard.

Overloaded, the gunboat struggled to pull away, but eventually it sped off in classic PT style, with Marines clinging to gun mounts. About 3 a.m., on the trip back to Vella Lavella, the boat’s gas tanks ran dry. PT-59 had to be towed to base by another boat.

Such missions took a toll on Jack’s weakened body. Back and stomach pain made sleep impossible. His weight sank to 120 pounds, and bouts of fever turned his skin a ghastly yellow. Doctors in mid-November found a “definite ulcer crater” and “chronic disc disease of the lower back.” On December 14, nine months after he arrived in the Pacific, he was ordered home.

Back in the States, Kennedy appeared to have lost the edge that drove him on PT-59. He jumped back into the nightlife scene and assorted romantic dalliances. Assigned in March to a cushy post in Miami, he joked, “Once you get your feet upon the desk in the morning, the heavy work of the day is done.”

By the time Kennedy launched his political career in 1946, he clearly recognized the PR value of the PT-109 story. “Every time I ran for office after the war, we made a million copies of [the Reader’s Digest] article to throw around,” he told Robert Donovan, author of PT-109: John F. Kennedy in World War II. Running for president, he gave out PT-109 lapel pins.

Americans loved the story and what they thought it said about their young president. Just before he was assassinated, Hollywood released a movie based on Donovan’s book and starring Cliff Robertson.

Still, Kennedy apparently couldn’t shake the deaths of his two men in the Solomons. After the Hersey story came out, a friend congratulated him and called the article a lucky break. Kennedy mused about luck and whether most success results from “fortuitous accidents.”

“I would agree with you that it was lucky the whole thing happened if the two fellows had not been killed.” That, he said, “rather spoils the whole thing for me.”

This story was originally published in MHQ Magazine.

MHQ Magazine Published / Source

Video Published & Released from Resource 29.05.2019

John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Born Brookline, Mass. (83 Beals Street) May 29, 1917

In all, Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy would have nine children, four boys and five girls. She kept notecards for each of them in a small wooden file box and made a point of writing down everything from a doctor’s visit to the shoe size they had at a particular age. John Fitzgerald Kennedy was named in honor of Rose’s father, John Francis Fitzgerald, the Boston Mayor popularly known as Honey Fitz. Before long, family and friends called this small blue-eyed baby, Jack. Jack was not a very healthy baby, and Rose recorded on his notecard the childhood diseases from which he suffered, such as: "whooping cough, measles, chicken pox."

On February 20, 1920 when Jack was not yet three years old, he became sick with scarlet fever, a highly contagious and then potentially life-threatening disease. His father, Joseph Patrick Kennedy, was terrified that little Jack would die. Mr. Kennedy went to the hospital every day to be by his son’s side, and about a month later Jack took a turn for the better and recovered. But Jack was never very healthy, and because he was always suffering from one ailment or another his family used to joke about the great risk a mosquito took in biting him – with some of his blood the mosquito was almost sure to die!

When Jack was three, the Kennedys moved to a new home a few blocks away from their old house in Brookline, a neighborhood just outside of Boston. It was a lovely house with twelve rooms, turreted windows, and a big porch. Full of energy and ambition, Jack’s father worked very hard at becoming a successful businessman. When he was a student at Harvard College and having a difficult time fitting in as an Irish Catholic, he swore to himself he would make a million dollars by the age of 35. There was a lot of prejudice against Irish Catholics in Boston at that time, but Joseph Kennedy was determined to succeed. Jack’s great-grandparents had come from Ireland and managed to provide for their families, despite many hardships. Jack’s grandfathers did even better for themselves, both becoming prominent Boston politicians. Jack, because of all his family had done, could enjoy a very comfortable life. The Kennedys had everything they needed and more.

By the time Jack was eight there were seven children altogether. Jack had an older brother, Joe; four sisters, Rosemary, Kathleen, Eunice, and Patricia; and a younger brother, Robert. Jean and Teddy hadn’t been born yet. Nannies and housekeepers helped Rose run the household.

KFC461P. Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. with sons Joe Jr. and Jack, Palm Beach, 1931

At the end of the school year, the Kennedy children would go to their summer home in Hyannis Port on Cape Cod where they enjoyed swimming, sailing, and playing touch football. The Kennedy children played hard, and they enjoyed competing with one another. Joseph Sr. encouraged this competition, especially among the boys.

He was a father with very high expectations and wanted the boys to win at sports and everything they tried. As he often said, "When the going gets tough, the tough get going." But sometimes these competitions went too far. One time when Joe suggested that he and Jack race on their bicycles, they collided head-on. Joe emerged unscathed while Jack had to have twenty-eight stitches. Because Joe was two years older and stronger than Jack, whenever they fought, Jack would usually get the worst of it. Jack was the only sibling who posed any real threat to Joe’s dominant position as the oldest child.

Jack was very popular and had many friends at Choate, a boarding school for adolescent boys in Connecticut. He played tennis, basketball, football, and golf and also enjoyed reading. His friend Lem Billings remembers how unusual it was that Jack had a daily subscription to the New York Times. Jack had a "clever, individualist mind," his Head Master once noted, though he was not the best student. He did not always work as hard as he could, except in history and English, which were his favorite subjects.

"Now Jack," his father wrote in a letter one day, "I don’t want to give the impression that I am a nagger, for goodness knows I think that is the worse thing any parent can be, and I also feel that you know if I didn’t really feel you had the goods I would be most charitable in my attitude toward your failings. After long experience in sizing up people I definitely know you have the goods and you can go a long way…It is very difficult to make up fundamentals that you have neglected when you were very young, and that is why I am urging you to do the best you can. I am not expecting too much, and I will not be disappointed if you don’t turn out to be a real genius, but I think you can be a really worthwhile citizen with good judgment and understanding."

Jack graduated from Choate and entered Harvard in 1936, where Joe was already a student. Like his brother Joe, Jack played football. He was not as good an athlete as Joe but he had a lot of determination and perseverance. Unfortunately, one day while playing he ruptured a disk in his spine. Jack never really recovered from this accident and his back continued to bother him for the rest of his life.

The two eldest boys were attractive, agreeable, and intelligent young men and Mr. Kennedy had high hopes for them both. However, it was Joe who had announced to everyone when he was a young boy that he would be the first Catholic to become President. No one doubted him for a moment. Jack, on the other hand, seemed somewhat less ambitious. He was active in student groups and sports and he worked hard in his history and government classes, though his grades remained only average.

Late in 1937, Mr. Kennedy was appointed United States Ambassador to England and moved there with his whole family, with the exception of Joe and Jack who were at Harvard. Because of his father’s job, Jack became very interested in European politics and world affairs. After a summer visit to England and other countries in Europe, Jack returned to Harvard more eager to learn about history and government and to keep up with current events.

Joe and Jack frequently received letters from their father in England, who informed them of the latest news regarding the conflicts and tensions that everyone feared would soon blow up into a full-scale war. Adolph Hitler ruled Germany and Benito Mussolini ruled Italy. They both had strong armies and wanted to take land from other countries. On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland and World War II began.

By this time, Jack was a senior at Harvard and decided to write his thesis on why Great Britain was unprepared for war with Germany. It was later published as a book called Why England Slept. In June 1940, Jack graduated from Harvard. His father sent him a cablegram from London: "TWO THINGS I ALWAYS KNEW ABOUT YOU ONE THAT YOU ARE SMART TWO THAT YOU ARE A SWELL GUY LOVE DAD."

World War II and a Future in Politics

Soon after graduating, both Joe and Jack joined the Navy. Joe was a flyer and sent to Europe, while Jack was made Lieutenant (Lt.) and assigned to the South Pacific as commander of a patrol torpedo boat, the PT-109.

Lt. Kennedy had a crew of twelve men whose mission was to stop Japanese ships from delivering supplies to their soldiers. On the night of August 2, 1943, Lt. Kennedy’s crew patrolled the waters looking for enemy ships to sink. A Japanese destroyer suddenly became visible. But it was traveling at full speed and headed straight at them. Holding the wheel, Lt. Kennedy tried to swerve out of the way, but to no avail. The much larger Japanese warship rammed the PT-109, splitting it in half and killing two of Lt. Kennedy’s men. The others managed to jump off as their boat went up in flames. Lt. Kennedy was slammed hard against the cockpit, once again injuring his weak back. Patrick McMahon, one of his crew members, had horrible burns on his face and hands and was ready to give up. In the darkness, Lt. Kennedy managed to find McMahon and haul him back to where the other survivors were clinging to a piece of the boat that was still afloat. At sunrise, Lt. Kennedy led his men toward a small island several miles away. Despite his own injuries, Lt. Kennedy was able to tow Patrick McMahon ashore, a strap from McMahon’s life jacket clenched between his teeth. Six days later two native islanders found them and went for help, delivering a message Jack had carved into a piece of coconut shell. The next day, the PT-109 crew was rescued. Jack’s brother Joe was not so lucky. He died a year later when his plane blew up during a dangerous mission in Europe.

When he returned home, Jack was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for his leadership and courage. With the war finally coming to an end, it was time to choose the kind of work he wanted to do. Jack had considered becoming a teacher or a writer, but with Joe’s tragic death suddenly everything changed. After serious discussions with Jack about his future, Joseph Kennedy convinced him that he should run for Congress in Massachusetts' eleventh congressional district, where he won in 1946. This was the beginning of Jack’s political career. As the years went on, John F. Kennedy, a Democrat, served three terms (six years) in the House of Representatives, and in 1952 he was elected to the US Senate.

Soon after being elected senator, John F. Kennedy, at 36 years of age, married 24 year-old Jacqueline Bouvier, a writer with the Washington Times-Herald. Unfortunately, early on in their marriage, Senator Kennedy’s back started to hurt again and he had two serious operations. While recovering from surgery, he wrote a book about several US Senators who had risked their careers to fight for the things in which they believed. The book, called Profiles in Courage, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for biography in 1957. That same year, the Kennedys’ first child, Caroline, was born.

John F. Kennedy was becoming a popular politician. In 1956 he was almost picked to run for vice president. Kennedy nonetheless decided that he would run for president in the next election.

He began working very long hours and traveling all around the United States on weekends. On July 13, 1960 the Democratic party nominated him as its candidate for president. Kennedy asked Lyndon B. Johnson, a senator from Texas, to run with him as vice president. In the general election on November 8, 1960, Kennedy defeated the Republican Vice President Richard M. Nixon in a very close race. At the age of 43, Kennedy was the youngest man elected president and the first Catholic. Before his inauguration, his second child, John Jr., was born. His father liked to call him John-John.

John F. Kennedy Becomes The 35th President of the United States

John F. Kennedy was sworn in as the 35th president on January 20, 1961. In his inaugural speech he spoke of the need for all Americans to be active citizens. "Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country," he said. He also asked the nations of the world to join together to fight what he called the "common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself." President Kennedy, together with his wife and two children, brought a new, youthful spirit to the White House. The Kennedys believed that the White House should be a place to celebrate American history, culture, and achievement. They invited artists, writers, scientists, poets, musicians, actors, and athletes to visit them. Jacqueline Kennedy also shared her husband's interest in American history. Gathering some of the finest art and furniture the United States had produced, she restored all the rooms in the White House to make it a place that truly reflected America’s history and artistic creativity. Everyone was impressed and appreciated her hard work.

The White House also seemed like a fun place because of the Kennedys’ two young children, Caroline and John-John. There was a pre-school, a swimming pool, and a tree-house outside on the White House lawn. President Kennedy was probably the busiest man in the country, but he still found time to laugh and play with his children.

However, the president also had many worries. One of the things he worried about most was the possibility of nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union. He knew that if there was a war, millions of people would die. Since World War II, there had been a lot of anger and suspicion between the two countries but never any shooting between Soviet and American troops. This 'Cold War', which was unlike any other war the world had seen, was really a struggle between the Soviet Union's communist system of government and the United States' democratic system. Because they distrusted each other, both countries spent enormous amounts of money building nuclear weapons. There were many times when the struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States could have ended in nuclear war, such as in Cuba during the 1962 missile crisis or over the divided city of Berlin.

President Kennedy worked long hours, getting up at seven and not going to bed until eleven or twelve at night, or later. He read six newspapers while he ate breakfast, had meetings with important people throughout the day, and read reports from his advisers. He wanted to make sure that he made the best decisions for his country. "I am asking each of you to be new pioneers in that New Frontier," he said. The New Frontier was not a place but a way of thinking and acting. President Kennedy wanted the United States to move forward into the future with new discoveries in science and improvements in education, employment and other fields. He wanted democracy and freedom for the whole world.

One of the first things President Kennedy did was to create the Peace Corps. Through this program, which still exists today, Americans can volunteer to work anywhere in the world where assistance is needed. They can help in areas such as education, farming, health care, and construction. Many young men and women have served as Peace Corps volunteers and have won the respect of people throughout the world.

President Kennedy was also eager for the United States to lead the way in exploring space. The Soviet Union was ahead of the United States in its space program and President Kennedy was determined to catch up. He said, "No nation which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in this race for space." Kennedy was the first president to ask Congress to approve more than 22 billion dollars for Project Apollo, which had the goal of landing an American man on the moon before the end of the decade.

President Kennedy had to deal with many serious problems here in the United States. The biggest problem of all was racial discrimination. The US Supreme Court had ruled in 1954 that segregation in public schools would no longer be permitted. Black and white children, the decision mandated, should go to school together. This was now the law of the land. However, there were many schools, especially in southern states, that did not obey this law. There was also racial segregation on buses, in restaurants, movie theaters, and other public places.

Thousands of Americans joined together, people of all races and backgrounds, to protest peacefully this injustice.

Martin Luther King Jr. was one of the famous leaders of the movement for civil rights. Many civil rights leaders didn’t think President Kennedy was supportive enough of their efforts. The President believed that holding public protests would only anger many white people and make it even more difficult to convince the members of Congress who didn't agree with him to pass civil rights laws. By June 11, 1963, however, President Kennedy decided that the time had come to take stronger action to help the civil rights struggle. He proposed a new Civil Rights bill to the Congress, and he went on television asking Americans to end racism. "One hundred years of delay have passed since President Lincoln freed the slaves, yet their heirs, their grandsons, are not fully free," he said. "This Nation was founded by men of many nations and backgrounds…[and] on the principle that all men are created equal." President Kennedy made it clear that all Americans, regardless of their skin color, should enjoy a good and happy life in the United States.

The President is Shot

On November 21, 1963, President Kennedy flew to Texas to give several political speeches. The next day, as his car drove slowly past cheering crowds in Dallas, shots rang out. Kennedy was seriously wounded and died a short time later. Within a few hours of the shooting, police arrested Lee Harvey Oswald and charged him with the murder. On November 24, another man, Jack Ruby, shot and killed Oswald, thus silencing the only person who could have offered more information about this tragic event. The Warren Commission was organized to investigate the assassination and to clarify the many questions which remained.

The Legacy of John F. Kennedy

President Kennedy's death caused enormous sadness and grief among all Americans. Most people still remember exactly where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news. Hundreds of thousands of people gathered in Washington for the President's funeral, and millions throughout the world watched it on television.

As the years have gone by and other presidents have written their chapters in history, John Kennedy's brief time in office stands out in people's memories for his leadership, personality, and accomplishments. Many respect his coolness when faced with difficult decisions--like what to do about Soviet missiles in Cuba in 1962. Others admire his ability to inspire people with his eloquent speeches. Still others think his compassion and his willingness to fight for new government programs to help the poor, the elderly and the ill were most important. Like all leaders, John Kennedy made mistakes, but he was always optimistic about the future. He believed that people could solve their common problems if they put their country's interests first and worked together.